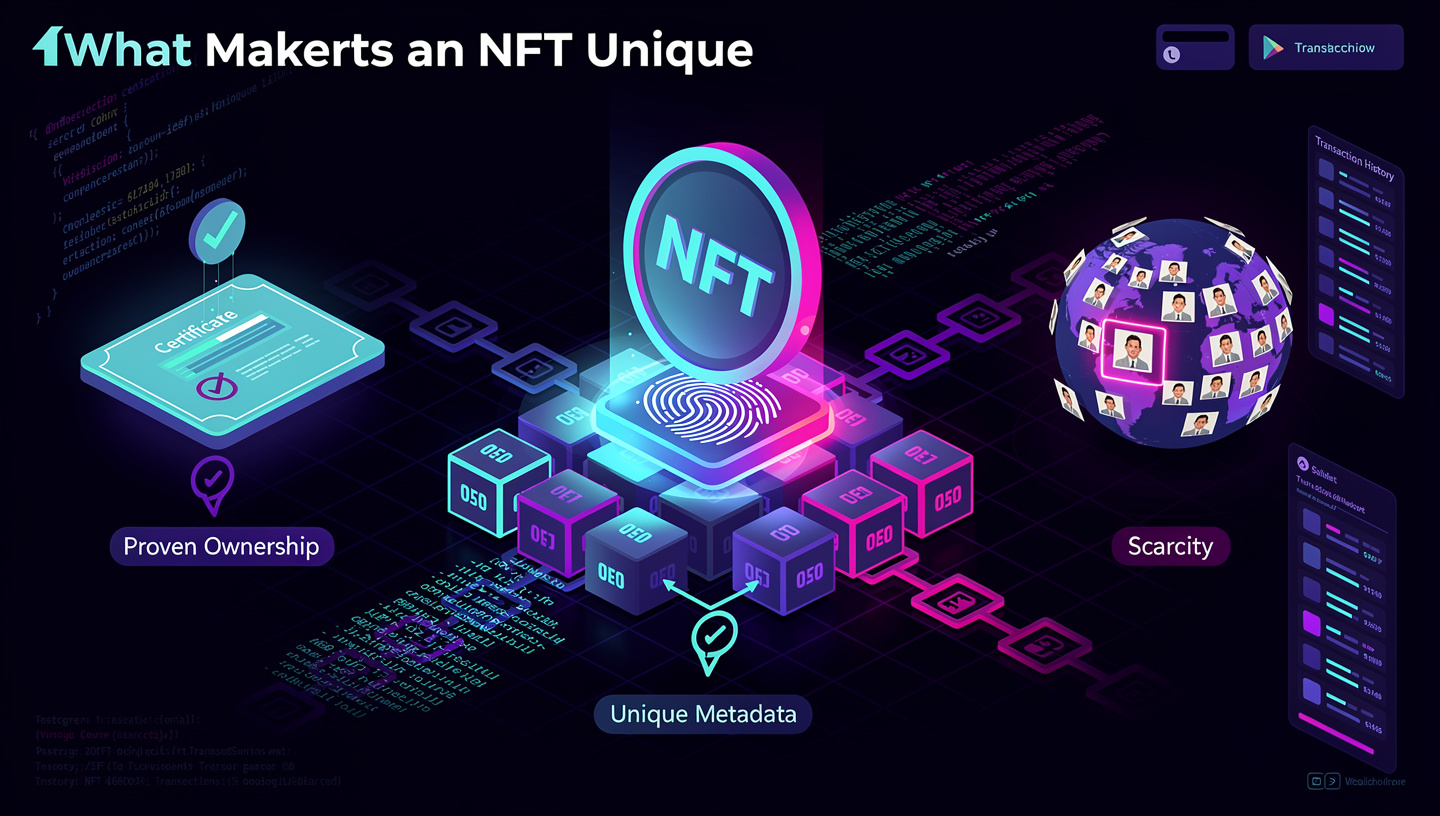

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have evolved from speculative digital collectibles into foundational components of programmable ownership. While public discourse often reduces NFTs to profile pictures or volatile assets, the deeper innovation lies in how they encode uniqueness at the protocol level.

The core question—what makes an NFT unique?—cannot be answered by surface-level attributes such as artwork or metadata. The uniqueness of an NFT is cryptographic, structural, and economic. It is enforced by blockchain consensus, standardized token contracts, and immutable state transitions. Unlike fungible assets such as Bitcoin or fiat currency, NFTs are architected to represent discrete, non-interchangeable units of value.

This article examines NFT uniqueness from first principles: cryptographic identity, token standards, metadata architecture, scarcity engineering, provenance tracking, composability, and economic design. It moves beyond superficial explanations and analyzes NFTs as deterministic, programmable artifacts embedded in distributed ledger systems.

1. Defining Non-Fungibility in Economic and Cryptographic Terms

1.1 Fungibility vs. Non-Fungibility

In economics, a fungible good is interchangeable with another unit of the same kind. One unit of a currency is equivalent to any other unit of equal denomination. Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum are fungible by design; each token within the same contract is identical in value and function.

Non-fungibility, by contrast, denotes uniqueness. A non-fungible asset cannot be replaced by another identical unit because no two units share the same attributes or identity. In blockchain systems, this uniqueness is not philosophical—it is encoded in smart contract logic and verified by network consensus.

1.2 Cryptographic Identity as the Foundation

An NFT’s uniqueness originates from:

- A smart contract address

- A token ID

- A specific blockchain state

Together, these form a globally unique tuple:

(blockchain, contract_address, token_id)

No other asset can replicate that exact combination within the same chain. Even if metadata is duplicated, the contract-token pairing remains singular.

2. Smart Contracts and the Architecture of Uniqueness

2.1 Token Standards: Formalizing Uniqueness

On Ethereum, NFT behavior is standardized primarily through:

- ERC-721

- ERC-1155

ERC-721 enforces one-to-one ownership mapping. Each token ID corresponds to a single owner address. It guarantees non-fungibility at the protocol level.

ERC-1155 introduces a semi-fungible architecture. Some token IDs may represent multiple identical units, while others remain unique. This allows hybrid asset modeling within one contract.

Uniqueness is therefore not a marketing attribute—it is a property enforced by code.

2.2 Token ID and Deterministic Differentiation

Each NFT is assigned a token ID, typically an integer. This ID:

- Is immutable after minting.

- Cannot collide within the same contract.

- Serves as the index for metadata retrieval.

Even if two NFTs reference identical images, differing token IDs guarantee cryptographic distinction.

3. Metadata: The Expressive Layer of Uniqueness

3.1 On-Chain vs Off-Chain Metadata

NFT uniqueness often relies on metadata stored:

- Directly on-chain (expensive but immutable)

- Off-chain via decentralized storage like IPFS

- On centralized servers (less secure)

Metadata typically includes:

- Name

- Description

- Media URI

- Trait attributes

- Properties

The URI pointer embedded in the smart contract links the token ID to its descriptive layer.

3.2 Trait-Based Differentiation

NFT collections frequently generate uniqueness through combinatorial trait systems:

- Background

- Accessories

- Color variations

- Rarity tiers

Even if generated algorithmically, the probability distribution of traits ensures statistically unique outputs. Rarity becomes mathematically encoded scarcity.

4. Immutability and Provenance

4.1 Blockchain Immutability

NFT uniqueness depends on blockchain immutability. Once minted:

- Ownership transfers are recorded permanently.

- Historical states cannot be retroactively altered.

- Provenance becomes verifiable.

The blockchain functions as a cryptographic ledger of custody.

4.2 Provenance as Value Amplifier

Provenance includes:

- Mint timestamp

- Original creator

- Transfer history

- Marketplace interactions

An NFT minted by a known creator on a specific block height has historical significance. Provenance transforms uniqueness into traceable narrative.

5. Scarcity Engineering

5.1 Artificial vs Enforced Scarcity

Digital assets are infinitely copyable at the file level. NFTs solve this by shifting scarcity from content to ownership records.

Scarcity is enforced by:

- Fixed supply caps

- Limited mint windows

- Controlled issuance schedules

Unlike physical scarcity, NFT scarcity is contractual and algorithmic.

5.2 Verifiable Supply

Anyone can query a contract to verify:

- Total supply

- Minted tokens

- Burned tokens

Scarcity is transparent and machine-verifiable.

6. Composability and Interoperability

6.1 NFTs as Programmable Primitives

NFT uniqueness extends beyond static identity. They can:

- Grant access rights

- Unlock software features

- Represent in-game assets

- Act as collateral

In ecosystems such as Solana or Polygon, NFTs function as composable modules integrated into DeFi, gaming, and identity protocols.

6.2 Cross-Protocol Integration

NFTs can interact with:

- Lending platforms

- Staking contracts

- Governance systems

Their uniqueness allows differentiated treatment across applications.

7. On-Chain Art and Autonomous NFTs

Some NFTs embed full generative logic directly in smart contracts. Projects on Ethereum have demonstrated:

- Fully on-chain SVG rendering

- Deterministic generative algorithms

- Immutable artistic output

In such cases, uniqueness derives not only from token ID but from algorithmic seed values.

8. Digital Signatures and Authenticity

Minting an NFT involves a transaction signed by a private key. That signature proves:

- The creator authorized the mint

- The origin wallet initiated issuance

If a recognized address deploys a contract, authenticity is cryptographically provable. Uniqueness is therefore tied to identity at the wallet level.

9. The Difference Between Copy and Ownership

Anyone can right-click and copy an NFT image. However:

- They cannot replicate the token ID.

- They cannot rewrite the contract state.

- They cannot forge blockchain history.

Uniqueness resides in the ledger entry, not the file.

This distinction redefines digital property.

10. Tokenization of Real-World Assets

NFTs can represent:

- Real estate titles

- Event tickets

- Intellectual property

- Luxury goods

In such cases, uniqueness reflects off-chain claims anchored to on-chain identifiers. The NFT becomes a cryptographic pointer to legal or physical rights.

11. Market Dynamics and Perceived Uniqueness

Economic uniqueness differs from structural uniqueness. All NFTs are technically unique. Not all are economically valuable.

Value depends on:

- Cultural relevance

- Creator reputation

- Community strength

- Utility integration

- Liquidity depth

Structural uniqueness is necessary but insufficient for price appreciation.

12. Limitations and Attack Vectors

NFT uniqueness can be undermined by:

- Mutable metadata links

- Centralized hosting

- Smart contract vulnerabilities

- Counterfeit collections

Verification requires:

- Contract address confirmation

- Marketplace validation

- On-chain inspection

Due diligence remains essential.

13. NFT Uniqueness vs Traditional Digital Assets

Traditional digital assets rely on centralized databases. Their uniqueness can be altered by administrators.

NFT uniqueness relies on:

- Decentralized consensus

- Cryptographic immutability

- Transparent auditability

This shift removes reliance on trusted intermediaries.

14. Identity, Credentials, and Soulbound Tokens

Emerging NFT models include non-transferable tokens for:

- Academic credentials

- Reputation scores

- Identity attestations

Uniqueness here extends to person-bound cryptographic identity systems.

15. Future Trajectory: Dynamic and Evolving NFTs

NFTs are evolving beyond static metadata into:

- Dynamic NFTs that change based on events

- NFTs tied to oracles

- NFTs reflecting real-time data feeds

Uniqueness may become state-dependent rather than static.

Conclusion: The Multidimensional Nature of NFT Uniqueness

NFT uniqueness is not aesthetic—it is architectural.

It emerges from:

- Cryptographic identity (contract + token ID)

- Blockchain immutability

- Enforced scarcity

- Provenance tracking

- Programmable utility

- Economic context

An NFT is unique because distributed consensus guarantees it is. Its singularity is encoded in deterministic smart contract logic and preserved across time by decentralized validation.

Understanding NFT uniqueness requires shifting perspective from files to ledgers, from images to identifiers, from art to architecture.

The NFT is not the picture.

It is the cryptographic proof of ownership anchored in a trust-minimized system.

That is what makes it unique.