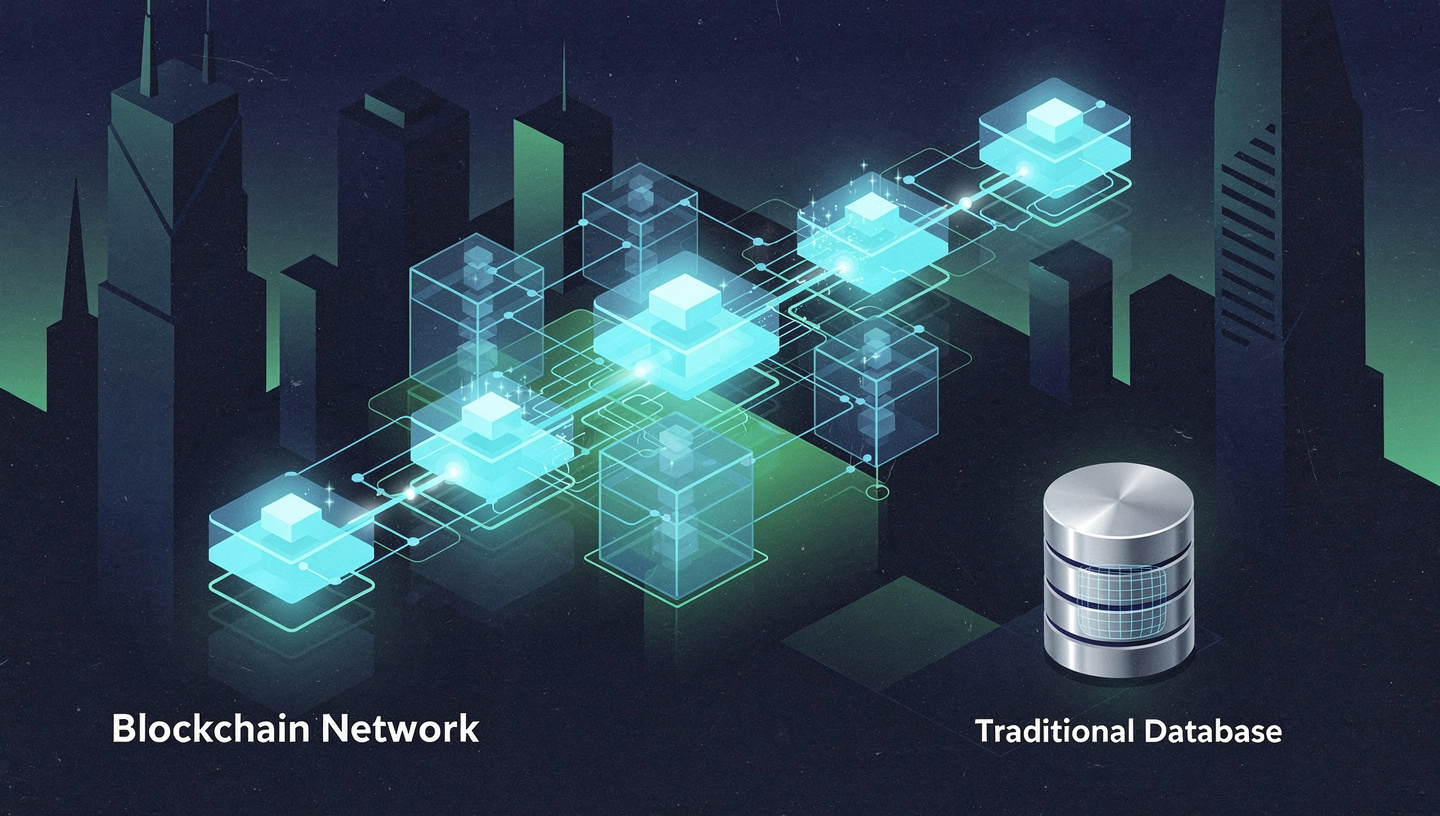

Reducing blockchain to “just a database” is not merely an oversimplification—it is a category error. A traditional database is an information storage and retrieval system governed by a centralized authority. A blockchain is a distributed state machine with embedded economic incentives, adversarial fault tolerance, and cryptographic finality. The two systems may both persist data, but they operate under entirely different trust models, coordination mechanisms, and security assumptions.

Understanding why blockchain isn’t just a database requires examining architecture, governance, consensus, cryptography, economic design, and adversarial resilience. When evaluated across these dimensions, it becomes clear that blockchain represents a new institutional technology—one that redefines how distributed systems establish trust without central administrators.

This article provides a detailed, research-oriented analysis of why blockchain is fundamentally distinct from traditional databases, and why this distinction matters for crypto infrastructure, decentralized finance (DeFi), and next-generation digital coordination systems.

1. What a Database Actually Is

A database is a structured system for storing, organizing, and retrieving data. Modern relational databases such as PostgreSQL or MySQL operate on several foundational principles:

- Centralized control

- Trusted administrator

- ACID compliance (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability)

- Role-based access permissions

- Efficient read/write operations

- Mutable records

Databases are optimized for performance, consistency, and operational control. They assume that a single authority—or coordinated administrative group—controls access, validates transactions, resolves conflicts, and can modify or delete data when necessary.

The trust model is explicit: users trust the database operator.

This assumption breaks down in adversarial environments where no central authority is universally trusted. Blockchain exists precisely to address that condition.

2. Blockchain as a Distributed State Machine

A blockchain is not merely a data store; it is a replicated state transition system maintained by a decentralized network of nodes.

In networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum, each node maintains an identical copy of the ledger. Instead of relying on a central administrator, these networks rely on:

- Cryptographic validation

- Consensus protocols

- Economic incentives

- Deterministic execution rules

Each block represents a batch of transactions that transitions the global state from one valid configuration to another. The blockchain enforces deterministic state transitions: given the same inputs, all nodes compute the same outputs.

This is categorically different from a database cluster, where consensus is internal and controlled by known operators. In blockchain systems, consensus must emerge across mutually untrusted participants.

3. The Trust Model: Trusted Authority vs Trust Minimization

Traditional databases operate under trusted authority assumptions. Blockchain systems are explicitly designed to minimize trust.

In a Database:

- The administrator can alter records.

- The hosting provider can shut down access.

- The organization can reverse transactions.

In a Blockchain:

- Data is append-only.

- History is computationally expensive to rewrite.

- No single participant can unilaterally alter state.

- Finality emerges from consensus and economic security.

This difference defines the core innovation of blockchain: trust minimization through distributed consensus.

The distinction is not about storage—it is about governance and control.

4. Consensus Mechanisms vs Database Replication

Databases often use replication protocols (e.g., primary-replica, multi-leader replication) to ensure availability. However, these systems assume cooperative participants within a single administrative domain.

Blockchain consensus mechanisms must function in adversarial environments.

Proof of Work

In Bitcoin, Proof of Work (PoW) ensures consensus through computational difficulty. Attackers must expend enormous energy to rewrite history.

Proof of Stake

In Ethereum (post-merge), Proof of Stake (PoS) secures the network via capital at risk. Validators stake assets that can be slashed for malicious behavior.

This economic layer has no equivalent in traditional databases.

Database replication is cooperative. Blockchain consensus is adversarial and incentive-aligned.

5. Immutability vs Editability

Databases are mutable by design. Records can be updated, deleted, or rewritten based on administrative privileges.

Blockchain is append-only. While technically not “immutable” in the absolute sense (since sufficient collusion could rewrite history), it is economically immutable.

Rewriting blockchain history requires:

- Controlling majority consensus power

- Sustaining economic cost

- Overcoming network-level monitoring

- Maintaining consistency across distributed nodes

This creates practical immutability—orders of magnitude stronger than database-level change logs.

Immutability is not a feature toggle. It is a systemic property of distributed consensus.

6. Economic Security vs Administrative Security

Databases rely on:

- Authentication systems

- Network firewalls

- Role-based permissions

- Organizational compliance

Blockchain relies on:

- Game theory

- Economic penalties

- Market competition

- Cryptographic guarantees

In PoS systems, validators risk financial loss. In PoW systems, attackers incur energy costs. Security is embedded in the protocol’s incentive structure.

Traditional databases do not integrate economic disincentives directly into data validation.

Blockchain security is endogenous; database security is external.

7. Censorship Resistance

A centralized database can:

- Freeze accounts

- Delete entries

- Restrict access

- Comply with political or corporate mandates

Blockchain networks resist censorship by design. As long as one honest node continues propagating valid transactions, inclusion remains possible.

In Bitcoin, no administrator can freeze funds globally. In Ethereum, smart contracts execute deterministically once deployed.

This property is incompatible with conventional database governance models.

8. Smart Contracts vs Stored Procedures

Databases support stored procedures and triggers. However, these operate within centralized administrative boundaries.

Smart contracts on Ethereum:

- Execute deterministically across thousands of nodes

- Cannot be modified unilaterally once deployed (without upgrade mechanisms)

- Enforce rules autonomously

- Manage digital assets without intermediaries

A smart contract is not just code stored in a database—it is self-enforcing logic secured by consensus.

9. Permissionless Participation

Databases are permissioned environments. Access is granted by administrators.

Public blockchains are permissionless:

- Anyone can run a node.

- Anyone can submit transactions.

- Anyone can verify history.

Permissionlessness enables open financial systems, decentralized governance, and censorship-resistant infrastructure.

This open participation model has no analogue in traditional enterprise databases.

10. Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Blockchain systems are designed to tolerate Byzantine faults—arbitrary malicious behavior from participants.

Databases typically tolerate crash faults (nodes going offline), not adversarial manipulation.

Blockchain consensus must assume:

- Malicious actors

- Collusion attempts

- Network partitioning

- Sybil attacks

The architecture reflects adversarial robustness at the protocol layer.

11. Tokenization and Native Assets

Databases do not natively represent scarce digital assets with consensus-backed ownership.

Blockchain networks embed asset ownership at the protocol layer. In Bitcoin, ownership is determined by cryptographic key control. In Ethereum, tokens conform to standards such as ERC-20 and ERC-721.

These assets:

- Are transferable without intermediaries

- Cannot be forged without consensus

- Are globally verifiable

This transforms blockchain into a financial settlement layer—not merely a storage engine.

12. Transparency and Auditability

Blockchain ledgers are publicly auditable.

Every transaction is:

- Timestamped

- Cryptographically signed

- Permanently recorded

- Globally verifiable

Traditional databases can provide audit logs, but these logs are maintained by the same authority they monitor.

Blockchain transparency is structurally independent of any single operator.

13. Governance and Protocol Evolution

Database governance is centralized.

Blockchain governance can be:

- On-chain (token-based voting)

- Off-chain (social consensus)

- Hybrid (core developer coordination)

The governance layer itself can be decentralized, as seen in Ethereum Improvement Proposals (EIPs) and Bitcoin Improvement Proposals (BIPs).

The system evolves without centralized ownership.

14. Performance Trade-Offs: Why Blockchain Is Slower

If blockchain were merely a database, it would be a poorly designed one—slow, expensive, and inefficient.

Blockchain intentionally sacrifices:

- Throughput

- Latency

- Storage efficiency

In exchange for:

- Trust minimization

- Decentralization

- Censorship resistance

- Economic security

This trade-off reflects design priorities, not engineering incompetence.

15. Real-World Implications

Understanding why blockchain isn’t just a database clarifies its appropriate use cases:

Suitable for:

- Decentralized finance (DeFi)

- Cross-border settlement

- Digital identity systems

- Tokenized assets

- Trust-minimized coordination

Unsuitable for:

- High-frequency transaction logging

- Centralized enterprise applications

- Internal company databases

Blockchain is not a universal replacement for databases. It is a coordination protocol for adversarial environments.

16. The Institutional Innovation

Blockchain represents a new form of institutional technology:

- It embeds rules in code.

- It aligns incentives economically.

- It distributes authority algorithmically.

- It reduces reliance on centralized intermediaries.

A database stores information.

A blockchain enforces agreement.

That distinction defines the paradigm shift.

Conclusion: Beyond Storage—Toward Trustless Infrastructure

Calling blockchain “just a database” ignores its consensus engine, economic incentives, adversarial fault tolerance, and decentralized governance.

A database answers the question:

“How do we store data efficiently?”

A blockchain answers:

“How do we agree on truth in a system without trusted authorities?”

This shift—from data management to trustless coordination—is the foundational breakthrough of crypto systems.

Blockchain is not merely a new database architecture.

It is a new trust architecture.