They Rewrite the Rules

Most people think crypto governance fails explosively. A hack. A rug. A sudden loss of funds.

That is a comforting illusion.

In reality, the most destructive governance attacks are slow, procedural, and perfectly legal within the system’s own rules. No private keys are stolen. No smart contracts are exploited. Every transaction is signed. Every vote is counted. Every step is “by the book.”

And yet the outcome is indistinguishable from a hostile takeover.

This is the uncomfortable truth: governance is the soft underbelly of crypto systems, and most participants dramatically underestimate how fragile it is. Code may be immutable, but control is not. Token-weighted voting may look objective, but power concentrates faster in governance than in almost any other layer of the stack.

If you do not understand governance attack vectors, you are not evaluating protocol risk. You are simply hoping.

This article breaks governance attacks down with the rigor they deserve—not as abstract threats, but as repeatable, structural failure modes that appear again and again across DAOs, L1s, L2s, DeFi protocols, and on-chain treasuries.

What Is a Governance Attack (and What It Is Not)

A governance attack is any coordinated action that captures or redirects protocol decision-making in a way that benefits an attacker at the expense of the system, without necessarily violating the protocol’s explicit rules.

This definition matters.

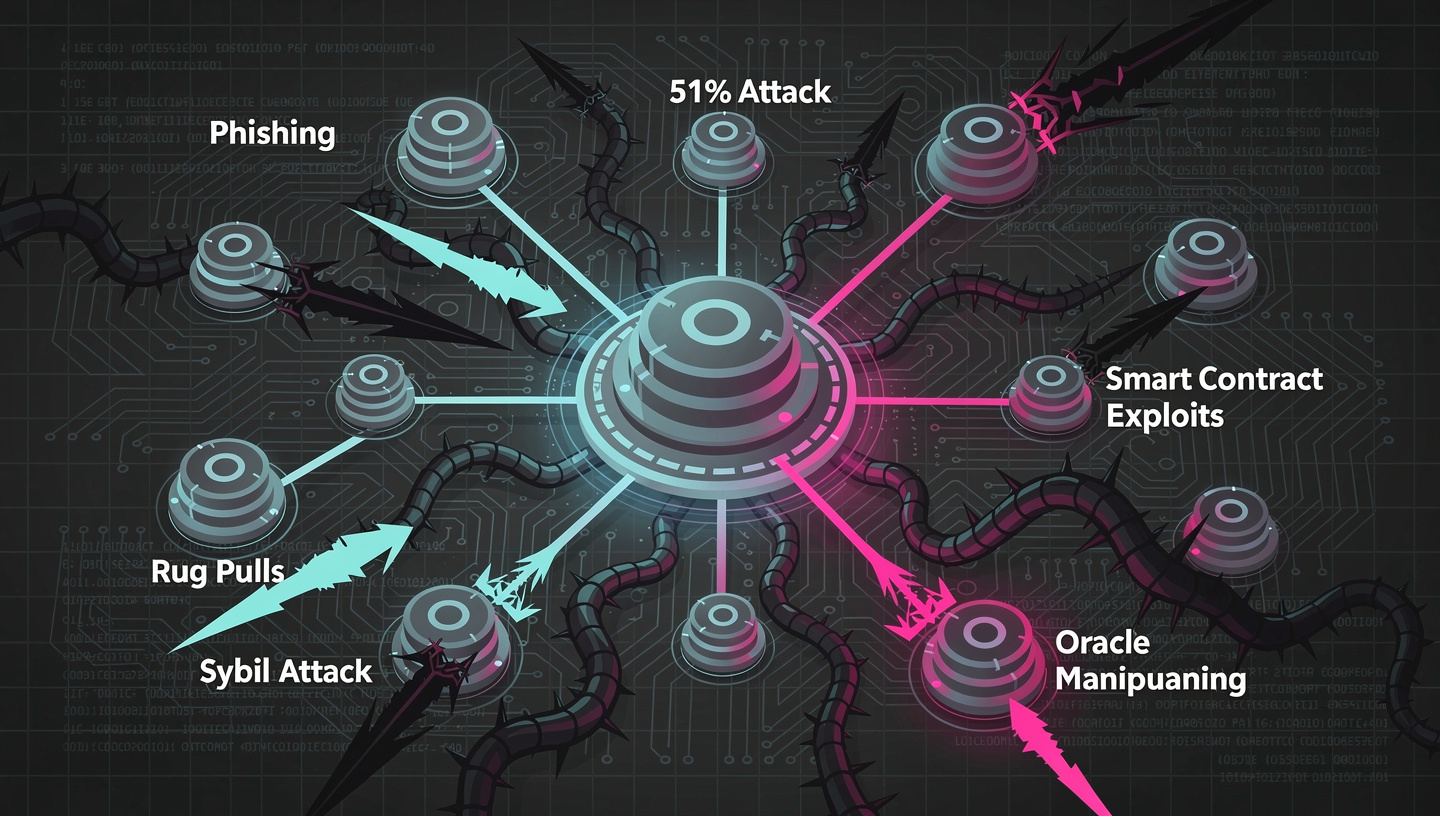

Governance attacks are often misunderstood because people confuse them with:

- Smart contract exploits

- Oracle manipulation

- Economic attacks like sandwiching or MEV

Those attacks target execution.

Governance attacks target authority.

They do not require bugs. They require incentives, coordination, asymmetries, and time.

In most cases, governance attacks succeed not because the system is poorly designed, but because it is naively designed—built under the assumption that token holders will behave like long-term stewards rather than economically rational actors.

Why Governance Is Structurally Vulnerable in Crypto

To understand governance attack vectors, you must first accept a core premise:

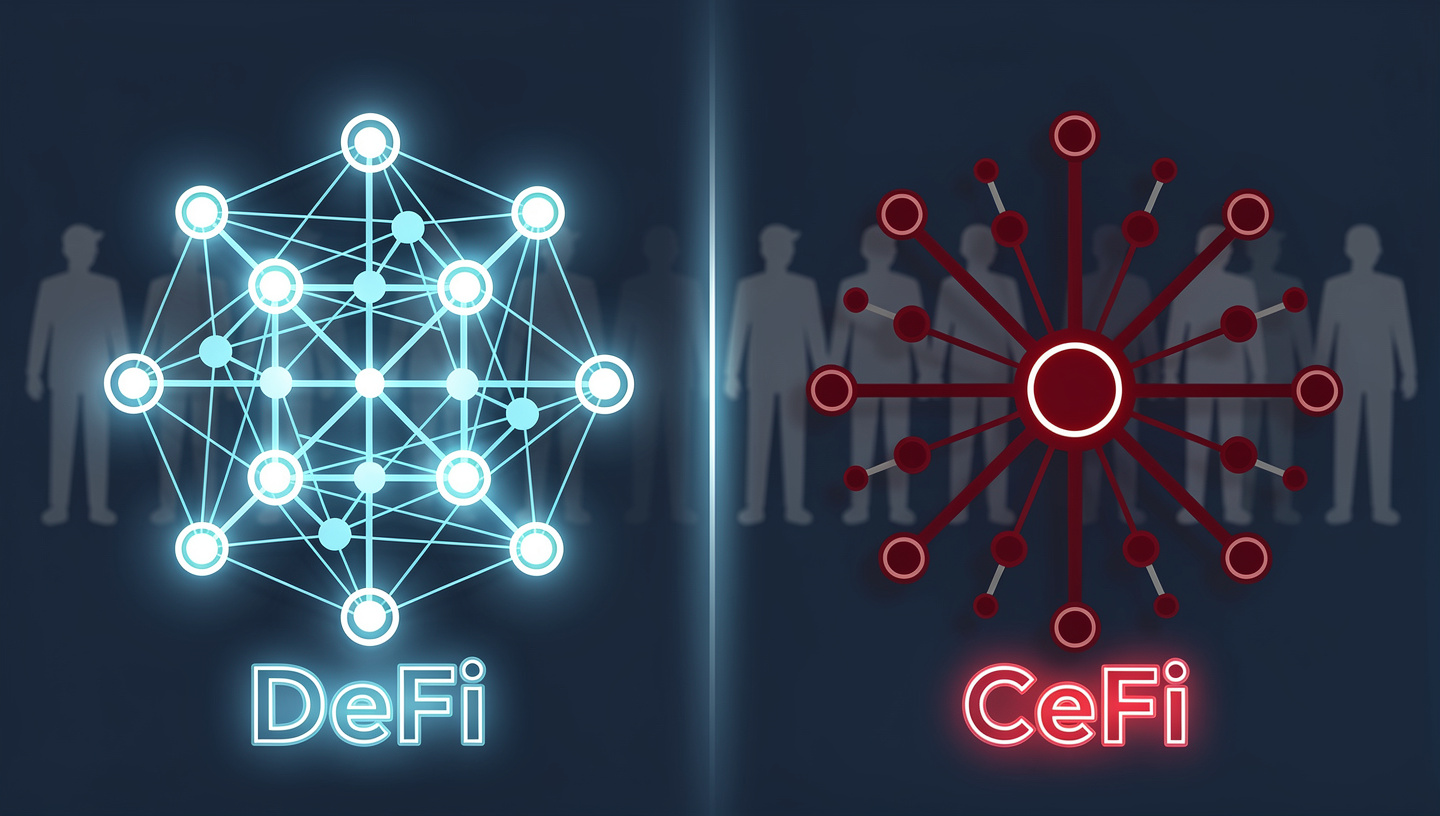

Crypto governance compresses power faster than traditional corporate or political systems.

There are three structural reasons for this.

1. Tokenization Turns Power into a Liquid Asset

In traditional systems, acquiring control is slow:

- Board seats take time.

- Voting rights are gated.

- Influence is reputational and political.

In crypto, governance power is often a transferable token.

This creates a market for control.

If governance power can be borrowed, accumulated, delegated, or temporarily acquired, then control becomes a financial strategy rather than a long-term commitment.

2. Participation Asymmetry Is Extreme

Most token holders do not vote.

A smaller subset delegates blindly.

An even smaller subset actually proposes changes.

This means governance outcomes are often determined by single-digit percentages of total token supply. In some protocols, effective control can be achieved with less than 5% ownership, if that ownership is active and coordinated.

3. Governance Moves Slower Than Capital

Capital can move in seconds.

Governance processes take days or weeks.

Attackers exploit this mismatch by entering positions, voting, executing outcomes, and exiting before the broader community even understands what happened.

Primary Governance Attack Vectors in Crypto

Let us now examine the major governance attack vectors—not as isolated incidents, but as patterns.

1. Token Accumulation and Majority Capture

This is the most straightforward governance attack—and still the most underestimated.

How It Works

An attacker accumulates governance tokens through:

- Open market purchases

- OTC deals

- Liquidity mining incentives

- Strategic partnerships

- Early insider allocations

Once a voting threshold is reached, the attacker can:

- Pass malicious proposals

- Block defensive proposals

- Modify treasury permissions

- Change protocol parameters to extract value

Importantly, nothing illegal or technically exploitative occurs.

Why It Succeeds

- Governance tokens are often underpriced relative to the value they control.

- Communities overestimate decentralization by counting token holders rather than voting power.

- There are rarely hard caps on voting concentration.

Real Risk Signal

If a protocol’s governance token has:

- Low voter turnout

- High concentration among top wallets

- Weak quorum requirements

Then majority capture is not hypothetical—it is latent.

2. Vote Buying and Governance Bribery

Vote buying does not require ownership.

It requires coordination.

Mechanics of Vote Buying

An attacker offers economic incentives to token holders or delegates in exchange for votes, typically through:

- Bribe markets

- Side agreements

- Off-chain coordination

- Token rewards conditional on proposal passage

Because voting is often pseudonymous, enforcement is trivial.

Why This Is Dangerous

Vote buying converts governance from a deliberative process into a short-term profit maximization game.

Delegates are incentivized to vote for:

- Higher emissions

- Treasury drains

- Parameter changes that favor extractive strategies

Long-term protocol health becomes irrelevant.

The Deeper Issue

If governance decisions are cheaper to buy than the value they unlock, governance will be captured. This is not a moral failure. It is an economic certainty.

3. Flash Loan Governance Attacks

Flash loans expose one of the most fundamental design flaws in token-based governance: time-agnostic voting power.

Attack Flow

- Borrow a large amount of governance tokens via a flash loan.

- Vote on a proposal within the same block or voting window.

- Execute or queue malicious changes.

- Repay the loan.

The attacker never bears long-term price risk.

Why Protocols Are Vulnerable

- Voting power is often calculated at a snapshot that does not account for holding duration.

- Protocols assume token ownership implies long-term alignment.

It does not.

Mitigations (Often Inadequate)

- Time-weighted voting

- Token lockups

- Delayed execution

Many protocols adopt these only after an incident.

4. Governance Proposal Injection

Not all governance attacks involve voting manipulation. Some involve proposal design.

The Subtlety of Proposal Attacks

Attackers craft proposals that:

- Bundle benign changes with malicious ones

- Use ambiguous language

- Exploit technical complexity

- Rely on voter fatigue

Because few voters read full proposals or audit execution code, malicious logic can pass unnoticed.

This Is Especially Dangerous When

- Proposals are long and technical

- Voting periods are short

- There is no formal review or simulation phase

Governance becomes a game of obscurity, not consensus.

5. Delegate Capture and Social Engineering

In delegate-based governance systems, capturing delegates is often more efficient than capturing tokens.

Methods of Delegate Capture

- Offering exclusive access or incentives

- Appealing to ideology or tribal alignment

- Leveraging reputation and social pressure

- Coordinated lobbying across communication channels

Once key delegates are aligned, outcomes are largely predetermined.

Structural Weakness

Delegates are often:

- Under-compensated

- Overloaded

- Poorly monitored by delegators

This creates fertile ground for influence operations.

6. Treasury Drain via Governance

The largest honeypot in any DAO is not the token—it is the treasury.

How Treasury Attacks Occur

Governance is used to approve:

- Excessive grants

- Self-dealing service contracts

- Overpriced acquisitions

- “Emergency” funding requests

These actions are framed as legitimate expenses but functionally extract value.

Why Communities Miss It

- Treasuries feel abstract

- Losses are distributed

- Attackers often present as contributors

Over time, the treasury empties—not through theft, but through sanctioned leakage.

Governance Attacks at the Base Layer

Governance attacks are not limited to DAOs and DeFi.

At the protocol layer, governance capture can influence:

- Validator requirements

- Slashing rules

- Inflation schedules

- Client diversity

In extreme cases, governance capture leads to de facto centralization, even if the network remains technically decentralized.

This is why serious protocol analysis must treat governance as a security layer, not a community feature.

How to Analyze Governance Risk in Practice

A rigorous governance risk assessment should include:

Token Distribution Analysis

- Top 10, 50, 100 holder concentration

- Exchange-controlled supply

- Vesting schedules and cliffs

Voting Behavior Metrics

- Average voter turnout

- Delegate dominance

- Proposal pass rates

Governance Process Design

- Quorum thresholds

- Voting duration

- Execution delays

- Proposal review mechanisms

Historical Governance Outcomes

- Who benefits from passed proposals

- Frequency of parameter changes

- Treasury outflows over time

Governance risk is measurable. Ignoring it is a choice.

The Hard Truth About “Decentralized Governance”

Decentralization is not binary.

Governance is not neutral.

And incentives always win.

A protocol with perfect code and weak governance will eventually be captured. Not by hackers, but by rational actors responding to poorly aligned incentives.

The future of crypto does not depend on eliminating governance attacks. That is unrealistic.

It depends on designing systems where governance capture is expensive, slow, visible, and reversible.

Until then, governance will remain the most elegant attack surface in the entire crypto stack—because it asks the system to defeat human behavior using rules written by humans.

That is a far harder problem than writing code.