Identity is not a profile. It is infrastructure.

In digital systems, identity determines who can transact, who can speak, who can build, and who can govern. It shapes incentives, regulates access, allocates power, and anchors trust. Yet most digital identity today is mediated by centralized authorities: governments issue passports, corporations manage logins, platforms curate reputations, and financial institutions determine compliance status.

The rise of crypto networks—beginning with Bitcoin and expanding through programmable platforms such as Ethereum—exposed a structural contradiction. These systems aim to remove central intermediaries from value exchange, yet identity remains one of the last domains governed by centralized control.

This tension has catalyzed a new field of innovation: decentralized identity (DID). The objective is not merely to digitize identity credentials, but to reconstruct identity as a user-controlled, cryptographically verifiable, and composable primitive within open networks.

This article examines the theoretical foundations, architectural components, cryptographic techniques, governance implications, and unresolved challenges of rethinking identity without central authorities. It provides a research-driven framework for designing decentralized identity systems that are robust, privacy-preserving, and interoperable at global scale.

1. The Centralized Identity Model: Structural Characteristics

Modern identity systems share common properties:

- Authority-Centric Issuance

A central institution validates and issues identity credentials (e.g., government IDs, corporate logins). - Siloed Data Repositories

Identity data is stored in centralized databases vulnerable to breach, misuse, and surveillance. - Revocation Through Administrative Control

Access can be denied or revoked unilaterally. - Opaque Data Usage

Users rarely control how their identity data is processed or shared.

These characteristics create systemic fragility:

- Single points of failure.

- Data breaches at population scale.

- Vendor lock-in.

- Censorship potential.

- Exclusion of unbanked or undocumented populations.

The architecture is not merely technological—it reflects governance assumptions: trust is delegated upward.

2. The Crypto Paradigm Shift: Trust Minimization

Crypto systems invert the trust model:

- Consensus replaces institutional authority.

- Cryptographic proofs replace institutional validation.

- Open protocols replace proprietary databases.

Satoshi Nakamoto demonstrated that distributed consensus could secure monetary value without a central bank. Subsequent innovation expanded this concept toward identity and credentials.

The question becomes:

If value can be transferred without centralized intermediaries, can identity also be verified without centralized custodians?

The answer lies in three pillars:

- Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI)

- Verifiable Credentials (VCs)

- Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs)

3. Self-Sovereign Identity: The Philosophical Core

Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) asserts that individuals should:

- Own and control their identity data.

- Decide who can access specific attributes.

- Store credentials in cryptographic wallets.

- Present proofs without exposing unnecessary information.

SSI shifts identity from institutional possession to user custody.

However, SSI is not synonymous with anonymity. Instead, it enables selective disclosure—proving specific attributes (e.g., age over 18) without revealing extraneous data (e.g., birth date, address).

This reconfiguration is foundational to innovation in crypto-native ecosystems.

4. Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs): The Structural Layer

A Decentralized Identifier is:

- A globally unique identifier.

- Anchored to a distributed ledger.

- Controlled via public-private key cryptography.

- Independent of centralized registries.

Unlike email addresses or usernames controlled by corporations, DIDs are permissionless and cryptographically verifiable.

Core Properties:

- Portability: Users can migrate across platforms without losing identity.

- Persistence: Identity does not depend on a single service provider.

- Cryptographic Control: Ownership is tied to key management, not institutional accounts.

DIDs allow identity resolution without central databases.

5. Verifiable Credentials: Cryptographic Trust Objects

Verifiable Credentials (VCs) are digitally signed attestations issued by trusted entities.

Example structure:

- Issuer: University

- Subject: Individual DID

- Claim: Degree completion

- Signature: Cryptographic proof

Unlike PDFs or centralized database entries, VCs are:

- Tamper-evident.

- Cryptographically verifiable.

- Portable across applications.

This enables a modular trust framework:

- Issuers attest.

- Holders control.

- Verifiers validate.

No central authority is required to mediate every transaction.

6. Zero-Knowledge Proofs: Privacy as Default

One of the most transformative innovations in decentralized identity is zero-knowledge cryptography.

A Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) allows a party to prove that a statement is true without revealing the underlying data.

For identity systems, this means:

- Proving age eligibility without revealing date of birth.

- Proving residency without disclosing address.

- Proving compliance without exposing financial history.

Advanced ZKP systems such as zk-SNARKs and zk-STARKs enable privacy-preserving identity verification at scale.

This innovation directly addresses one of the core weaknesses of centralized identity: overexposure of personal data.

7. Blockchain as Identity Anchor: Advantages and Tradeoffs

Distributed ledgers serve as:

- Tamper-resistant anchor points.

- Public key registries.

- Revocation registries.

However, storing personal data on-chain is fundamentally flawed due to immutability. Therefore, best practice architecture:

- Stores only identifiers and proofs on-chain.

- Keeps sensitive data off-chain.

- Uses cryptographic commitments for verification.

Platforms such as Ethereum have enabled identity protocols like ENS (Ethereum Name Service), while newer networks optimize for identity-specific throughput.

The challenge is balancing:

- Transparency

- Privacy

- Scalability

- Cost

8. Identity and Reputation: The Sybil Resistance Problem

In decentralized systems, identity must address Sybil attacks—where a single entity creates multiple pseudonymous identities.

Without central verification, how can systems prevent manipulation?

Approaches include:

- Proof-of-Personhood protocols

- Web-of-trust attestations

- Social graph validation

- Biometric cryptographic commitments

- Economic staking mechanisms

Each approach carries tradeoffs in privacy, scalability, and inclusivity.

This is one of the most active research domains in decentralized governance.

9. Regulatory Tensions: Compliance vs Sovereignty

Governments mandate identity verification through KYC (Know Your Customer) and AML (Anti-Money Laundering) regulations.

Centralized identity enables:

- Surveillance.

- Data aggregation.

- Enforcement efficiency.

Decentralized identity systems propose:

- Compliance via cryptographic proofs.

- Regulator-verifiable attestations.

- Privacy-preserving audit trails.

The future is unlikely to eliminate regulation; instead, innovation focuses on:

- Compliance without data hoarding.

- Selective disclosure rather than full exposure.

- Cryptographic auditability.

This redefines regulatory infrastructure rather than rejecting it.

10. Identity Wallets: The New User Interface

For decentralized identity to function, key management must become usable.

Identity wallets combine:

- Key custody.

- Credential storage.

- Selective disclosure tools.

- Cross-platform interoperability.

The usability problem is severe:

- Key loss = identity loss.

- Poor UX = low adoption.

Innovation areas include:

- Social recovery mechanisms.

- Multi-signature custody.

- Hardware security modules.

- MPC (Multi-Party Computation).

Identity innovation is not only cryptographic; it is deeply human-centered.

11. Interoperability: The Global Coordination Problem

Decentralized identity must interoperate across:

- Nations

- Platforms

- Blockchains

- Enterprises

Without standards, fragmentation will recreate silos.

Organizations such as the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) have proposed DID and VC standards, but real-world adoption remains uneven.

Interoperability requires:

- Shared schemas

- Standardized signature suites

- Cross-chain identity resolution

- Governance coordination

Failure to standardize risks protocol Balkanization.

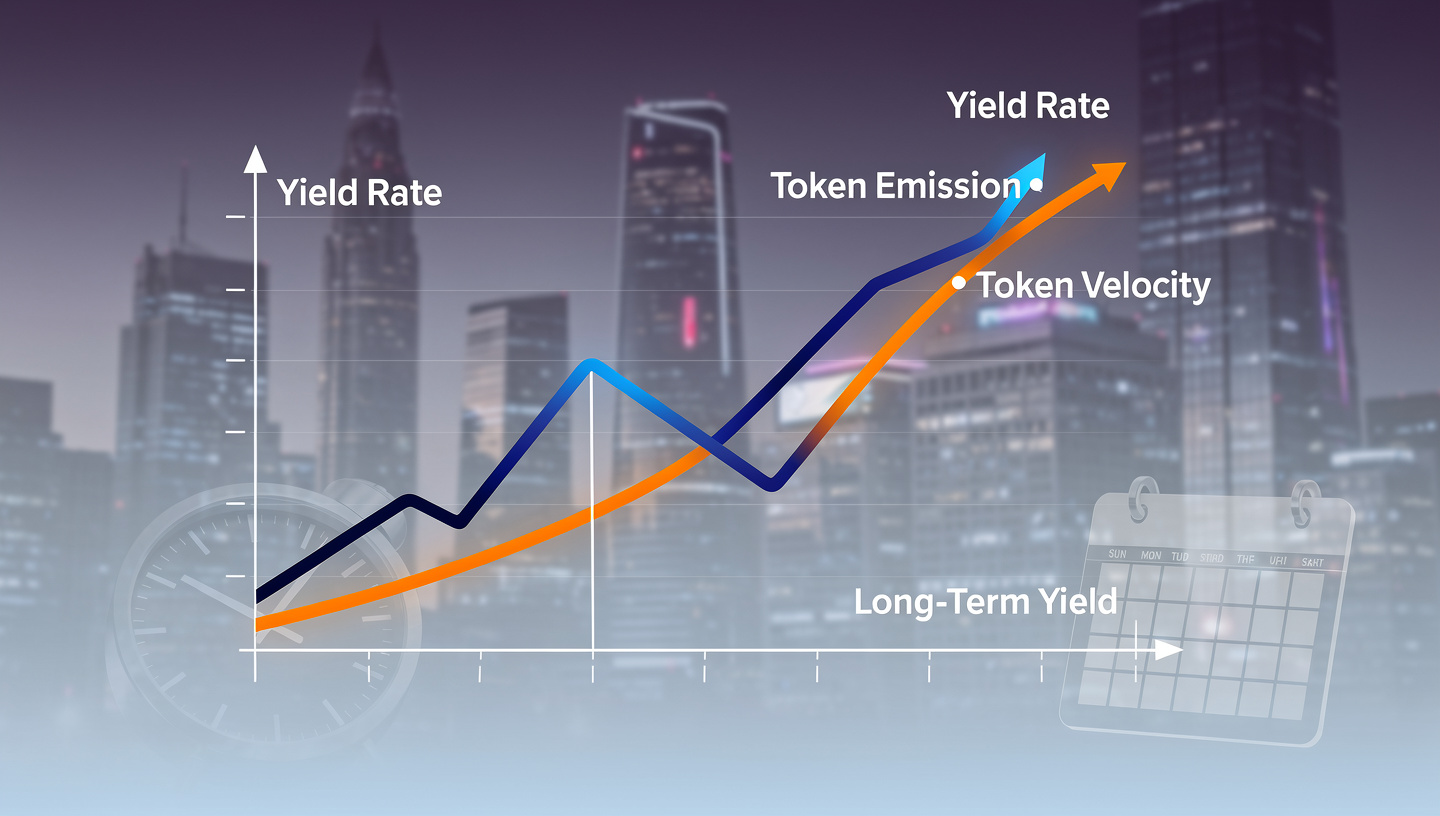

12. Economic Implications: Identity as Capital

In decentralized networks, identity becomes economically significant.

Identity influences:

- Credit scoring

- DAO governance weight

- Access to liquidity pools

- Reputation-based privileges

Unlike centralized credit bureaus, decentralized identity systems can embed programmable reputation.

This transforms identity into:

- A composable asset

- A governance credential

- A financial signal

However, it also raises concerns:

- Reputation lock-in

- Algorithmic bias

- On-chain discrimination

Innovation must incorporate fairness constraints.

13. Identity in DAO Governance

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) face identity dilemmas:

- One-token-one-vote creates plutocracy.

- One-person-one-vote requires personhood verification.

Proof-of-personhood protocols attempt to reconcile decentralization with democratic participation.

Without reliable identity mechanisms, DAO governance risks:

- Vote manipulation

- Collusion

- Sybil exploitation

Identity innovation is foundational to decentralized governance legitimacy.

14. Inclusion and Global Equity

Over one billion people lack formal identity documents.

Centralized identity systems exclude:

- Stateless individuals

- Refugees

- Informal workers

Decentralized identity can:

- Enable portable credentials.

- Allow peer-issued attestations.

- Reduce bureaucratic barriers.

However, digital access, hardware costs, and literacy remain constraints.

True inclusion requires:

- Offline-compatible verification

- Low-bandwidth solutions

- Hardware-agnostic systems

15. Threat Models and Attack Surfaces

Decentralized identity introduces new risks:

- Key compromise.

- Social engineering.

- Biometric spoofing.

- Metadata leakage.

- Correlation attacks.

Privacy by default requires:

- Minimizing persistent identifiers.

- Rotating keys.

- Avoiding on-chain personal data.

- Designing unlinkability into protocols.

Security architecture must be proactive, not reactive.

16. The Future: Identity as a Protocol Layer

Identity innovation in crypto is converging toward:

- Modular credential ecosystems.

- Cross-chain identity resolution.

- ZK-native compliance.

- Portable reputation layers.

- AI-integrated identity agents.

The long-term vision is identity as a protocol layer, not an application feature.

Just as TCP/IP underpins the internet, decentralized identity could underpin the trust layer of digital civilization.

Conclusion: From Control to Coordination

Rethinking identity without central authorities is not an ideological exercise. It is a systems engineering challenge.

The centralized model optimized for administrative control.

The decentralized model optimizes for coordination without coercion.

Innovation in decentralized identity requires:

- Cryptographic rigor.

- UX discipline.

- Regulatory interoperability.

- Economic fairness.

- Global standards alignment.

The objective is not anonymity at all costs.

The objective is programmable trust.

As crypto ecosystems mature beyond speculation into governance, finance, and digital infrastructure, identity becomes the decisive variable. Without it, decentralization collapses into chaos. With it, decentralized systems can scale responsibly.

The next decade of innovation will determine whether identity remains an instrument of institutional control—or becomes a user-controlled, cryptographically secured foundation for digital sovereignty.

The architecture is emerging. The challenge is execution.